.

At the sanatorium, Morris met Edith Grossman, whom he married in 1950. Edith had been selected for death immediately after arriving at Auschwitz, but had been rescued (literally taken out of the line for the gas chambers!) by several women whom she heard speaking Slovak. “I explained to them that I was not actually sick, but was put in the line because of a rash that I had developed because of an allergy to the grass we were forced to eat when we arrived at Auschwitz.” She was soon taken to Ravensbruck and then dispatched to Berlin to work as a forced laborer in a munitions factory for the duration of the war. She is the only survivor from the Grossman family.

Edith and her mother

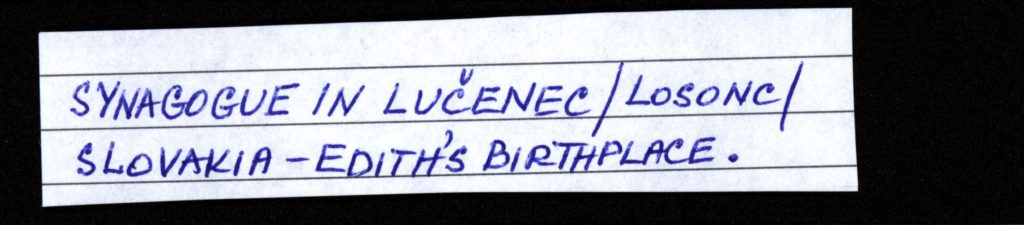

First Camel Ride in Israel, 1960

Edith at the Yiddish Book Center

Edith’s Oral History Interview with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

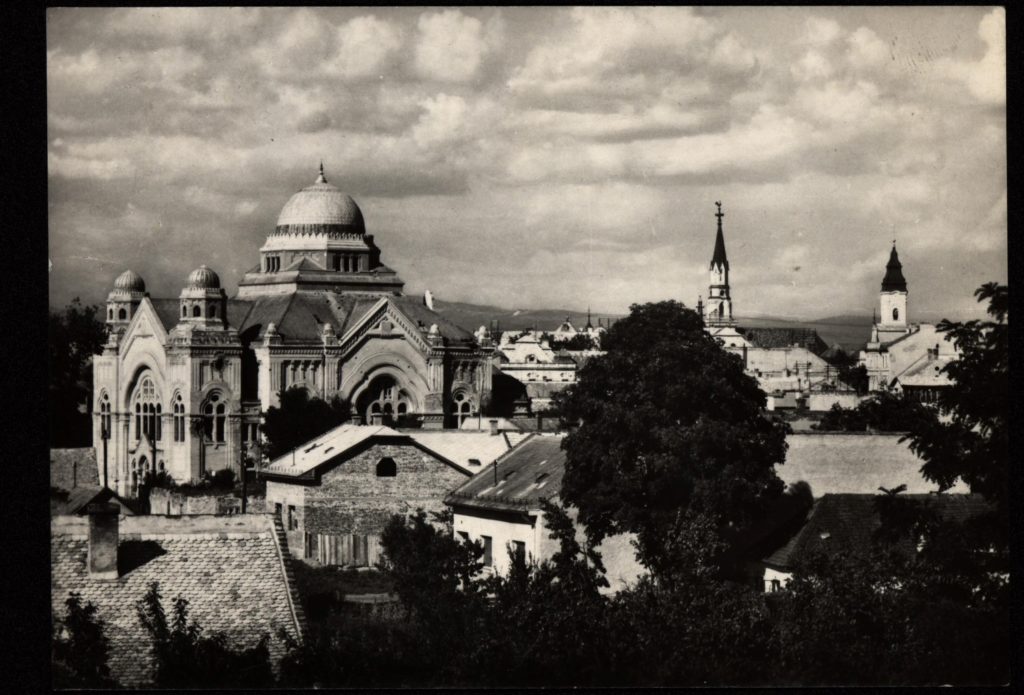

Edith Hollender was born to Josef and Irene (née Horowitz) Grossman on January 9, 1927 in Lučenec, Slovakia, growing up in the smaller nearby town of Filakovo. Her family mostly spoke Hungarian, but her father placed her in a Slovakian school in order to expand her language capability. Edith had one sister, Judith. Her father ran a general store and had a comfortable living. After grade 5, she had to travel six days a week the 16 miles to Lučenec for school. Edith describes life in her village.

After the Germans invaded, in 1942 her family was sent to the Lučenec ghetto while her father was sent to a work camp where he reportedly died in a bombing raid. After about 6-10 months, the remaining family were sent to Auschwitz. Edith was separated from her mother and sister on arrival and never again saw them. She was befriended by two Slovakian non-Jewish women who arranged for her transfer to a women’s work camp near Berlin. Russian soldiers liberated the camp and arranged for her transfer to Prague. When she arrived in Filakovo, only one uncle had survived. Edith was treated for tuberculosis at a Slovakian sanatorium in Crednitza (?) for two years where she met her husband, Morris, a native of eastern Czechoslovakia. Her husband’s sister had left him a house in Liberec when she left for New Jersey. They opened a store there.

Edith and her husband arranged papers to the U.S. through his sister and decided on Boston. She became employed by Harvard’s botany department classifying and cataloging plant

specimens from China. She never had children.

Article by D.G. Meyers referring to Edith’s private diary (Holocaust Literature and Interpretation, Fall 1999, Vol. 51, No. 54)