“What was Czechoslavakia like when you were growing up?”

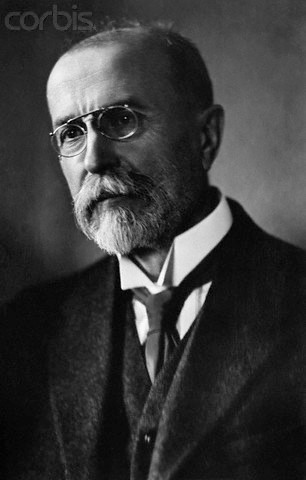

“It was a wonderful place, very free for Jews compared to most parts of Europe. When President Masaryk came to Muncasz, instead of going around in his carriage with the mayor of the city, he would go pick up Rabbi Shapiro, the chief Rabbi, and sit beside him in the coach so that the people could take an example from him that there should be no anti-Semitism”

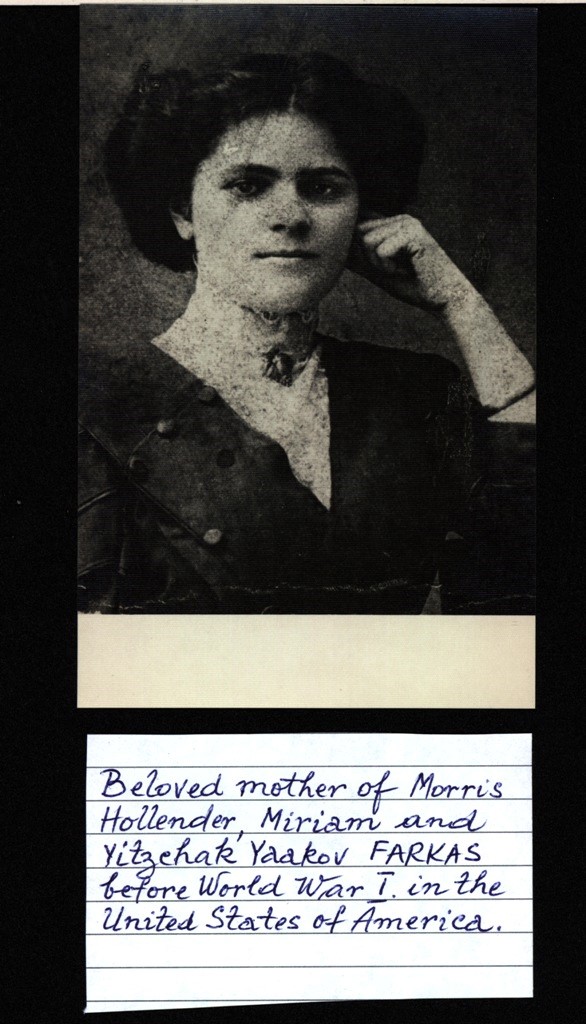

“Tell us about your grandmother.”

“My grandmother had a lot of common sense and was very much respected in the community. Her husband, Wolf Leib Farkas, was a kheyder (Jewish children’s primary school) teacher. He was very strict and very well educated. My grandmother would stay with us twice a year, around the time of the High Holidays and around Pesakh. She couldn’t read Hebrew and, between Rosh Hashona and Yom Kippur, she wanted to recite Avinu Malkeynu (the prayer that asks to be renewed in the book of life) every day – so I would recite each line and she would repeat it after me.”

“I often arrived at my Grandmother’s house very tired after a long day in both Talmud Torah and public school. Because of this she called me ‘der farshlofene ying,’ ‘the “sleepy boy’ – of course, she had no idea how active I had been during the day! She was very observant and carefully followed all of the traditional Jewish laws. One of her sons married Esther, a woman who kept her natural hair (instead of wearing a wig, as was customary among married women). Because of this, my grandmother wouldn’t even drink water at their house when she went to visit them. Esther became sick and died of cancer while she was still in her thirties. She died on a Friday night and, when she died, I remember hearing my Grandmother lamenting and crying for days. She was pleading to God for forgiveness for not honoring her daughter-in-law while she was still alive; along with many other traditional Jews, she believed that, if someone died on shabes, it was a sign that they had been truly righteous.”

“You mentioned that your grandfather gave part of your family farm over to a family of Gypsies. Do you remember anything about them?”

“When I was young, I had warts on my hands and they were bleeding always…also on my palms. Marishke, the Gypsy elder noticed it and said, ‘Young man, if you will go to the forest to pick blueberries, or raspberries, or something else, and you will find there a bone from a deceased animal, take that bone and circle it three times over every wart and say “Where I have the warts on my hand, there shall be flesh again.” One day my sister, Hentshe found a bone, and she said ‘Moyshele, I want to try what Mr. Marishka told you,” and, just for fun, she tried what he said. Some time passed and, one day in the morning I was washing my hands and she said “Oh, your hands are so smooth!,” and I said “Oh, the warts are gone!” And they never came back.”

“You mentioned that your mother was a very intelligent woman, in that she had a lot of common sense. Can you tell us an example of that?”

“Everybody in our town had their own chickens. We raised two-hundred-fifty or three-hundred chickens every year. They were part of our lives…we fed them with corn and all kinds of grains. One time a disease broke out that caused an infection in their intestines. Thousands and thousands of chickens were dying everywhere in the village, but our chickens were healthy and nobody could figure out what had happened, “Why do the Hollenders have their chickens and all of the other ones died? And the veterinarian came to our place and he said, “Mrs Hollender, you are feeding the chickens the same as everyone else in the village, with corn and grain and watered. Are you doing anything differently?” And she said ‘no, but since nothing goes to waste in our place, I collect the whey from making cheese and give it to the chickens instead of water. In the beginning they didn’t want to drink it, but they didn’t have anything else, so they had to drink the whey. And he said, ‘That’s it! That cleaned out their intestines, (so that) they didn’t get the disease.”